Author: Alan Swenson, VP of Interoperability at Kno2

There’s a lot to explain around the exceptions to information blocking. I will attempt to keep it simple, provide enough information to be meaningful, all while walking the line of pushing my word count from this being a blog to a novella…

In a companion blog, I talk about how the government is transitioning away from incentive-based regulations that promote interoperability over to some very real consequences to preventing the access, exchange, or use of electronic health information (EHI) as we see published in 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC).

Before I continue, let’s quickly revisit the definition for information blocking. As published in the Federal Register (45 CFR § 171.103) this is a complex definition with ambiguous words like “unreasonable”, “likely”, and “should know” as part of the requirements for each category of “actor” that will be liable for penalties.

So, is it safe to say that sharing is good, and withholding information is bad?

Maybe.

Broadly stated, Information Blocking is any restriction on sharing electronic health information (EHI). It doesn’t matter who is asking for it, why they’re asking for it, or what they plan to do with it. If someone wants to get rich by collecting and selling celebrity health records, they can ask for whatever they want, and if you don’t give it to them, that is information blocking.

You’re thinking, “Hold on; that’s ridiculous! HIPAA says…”

And you’re right. There are cases where it is completely reasonable, even necessary to NOT share information. The definition allows for cases “as required by law”—such as HIPAA—and also covered by “exceptions”.

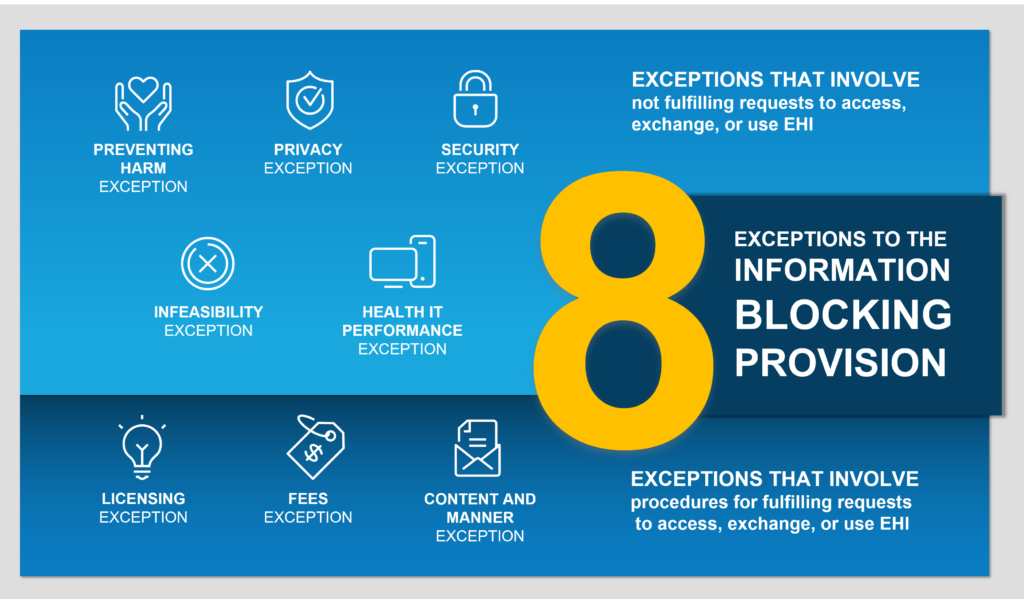

It is said that for every rule, there is an exception, and in the case of Information Blocking, there are actually eight exceptions. While “exceptions to the rule” often has a negative connotation, in this case the exceptions aren’t bad; they’re actually good, and organizations should leverage them when appropriate.

In the example I just gave, a provider could easily decline the request for the celebrity records, indicating that it’s not allowed under HIPAA, which is both a separate law and is also explicitly included in the Privacy Exception.

That said, to leverage an exception, you must actually meet the requirements of that exception. We’ve all heard stories of people being told, “I can’t do that because of HIPAA”, when it had nothing to do with HIPAA, or may have even been the opposite of what HIPAA allows. you can’t just claim you’re not sharing because of HIPAA and think you’re covered. If you’re expecting an exception to allow not sharing information, then you must understand what HIPAA actually says (or any other applicable law) and what it permits before you point to it.

Digging Deeper

Information Blocking is any interference—whether it actually prevented or just discouraged—sharing information, AND where there is not an exception that covers why you did not share.

The exceptions are broken up into two categories:

- Exceptions that involve not fulfilling requests to access, exchange, or use EHI.

- Exceptions that involve procedures for fulfilling requests to access, exchange, or use EHI.

Preventing Harm Exception

“First, do no harm.” This exception covers not sharing information, when that information would cause a risk of harm—particularly physical harm—to the patient or another person. I’ve heard a lot of concern and confusion around this one about emotional harm, or whether it is ok to have a “blanket” delay for the release of certain test results so that a clinician can review and potentially discuss the result with the patient. ONC has provided specific clarification that such delays are not covered by this exception and could constitute information blocking. Determination of risk of harm must be individualized with the professional judgment of the ordering clinician, and their relationship with the patient.

Privacy Exception

In protecting patient privacy, an actor is not required to use or disclose patient information in a way that violates other state or federal privacy laws. In my previous example of the celebrity record request, the Privacy Exception clearly covers not releasing those records due to HIPAA. This also covers things like an individual’s request to have their information not be shared, or requests where consent requirements are not met. Note, however, that in ONC’s examples of practices that may implicate information blocking they specifically call out requiring consent to exchange EHI for treatment even though not required by law. So, an organizational decision to require additional patient consent beyond HIPAA for all exchanges may actually be information blocking and you’ll want to review your organizational consent policies.

Security Exception

If a request for EHI presents a threat to the “confidentiality, integrity, and availability” of patient information, you may be able to point to this exception. This will need to be consistent and non-discriminatory, and tailored to specific security threats. It does not cover practices that claim to promote security but are “unreasonably broad and onerous”.

Infeasibility Exception

You may decline a request if it is “infeasible”. Many of the reasons why you wouldn’t respond may better fall into another exception. This one is intended to cover circumstances outside the control of the actor, such as natural disaster, war, etc. or inability to share the requested information because it cannot be unambiguously segmented from other information. The bar is rather high on using this exception, with others intended to be the primary focus.

Health IT Performance Exception

This covers cases such as your system being down for routine maintenance, or you are working to improve health IT performance, and that temporarily prevents you from sharing the requested information. Similar to other exceptions, it must be consistent and non-discriminatory.

Content and Manner Exception

There are two parts to this exception. Let’s say that today you are connected to Carequality for document exchange, but someone is asking you for FHIR resources. If you don’t have support yet for all of the requested FHIR resources, you could point to this exception to say that you can’t give them all of the information in the manner they requested, but you could respond to a document request through Carequality, providing the patient information in a C-CDA document.

The content piece of the exception is about the actual data that you share. Information blocking applies to requests for Electronic Health Information (EHI), which aligns with the HIPAA ePHI definition. However, not all EHI can easily be exchanged today, or have consistent standards for coding. Until October 6, 2022, you are only required to exchange the EHI elements that are part of USCDI (United States Core Data for Interoperability), a subset of EHI with required standards for coding of each element. Though if you are able to share more, you shouldn’t artificially limit your sharing to only USCDI.

Fees Exception

Information blocking does not prohibit charging fees to fulfil requests for EHI. If the request comes from an attorney or life insurance agency, or someone else who today you would charge a record request fee for that release of information, you could likely continue that under this exception. There are a number of requirements for the basis of the fee, including anti-competitive, consistency, non-discriminatory, etc. that you will want to review against your current fee requirements to ensure your fees are allowed under this exception.

Licensing Exception

If you are a health IT developer, health information network, etc. that requires licensing—including license fees—for the use of your interoperability elements, this exception protects you if your customers are unable to exchange information because they have not licensed the necessary functionality. You will want to ensure your licensing requirements meet the exception, e.g., non-discriminatory, “reasonable” royalty fees, etc.

For more complete information, view the fact sheet for all eight exceptions published on HealthIT.gov.

Providers need to focus on Connectivity

With so many competing technologies available, providers and health IT developers need to consider the simplest path to broad connectivity across all of the national healthcare networks, leveraging standards-based methods for secure and efficient exchange of patient information. Ideally for providers, those capabilities should be available within their electronic health record (EHR).

The good news…every 2015 Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) system is capable of sending and receiving Direct Secure Messages. However, some providers may not realize they have this functionality because it’s often built into the EHR and not labeled as “Direct Messaging”, with different terminology used by each vendor to describe it.

If that same EHR has also connected to Carequality—either directly or through an Implementer of the Carequality Framework, like Kno2—providers using their technology are also capable of using query-based exchange for on-demand record retrieval rather than sending a record request and waiting for a response. Participating in Carequality, which includes providers connected through the CommonWell Health Alliance®, enables simple access to patient information, providing a great way for providers to automatically respond to requests without human intervention. With 600K care providers, 50K clinics and 2800+ hospitals already participating via Carequality/CommonWell, 90+ million records are being exchanged every month.

FHIR (Fast Interoperability Healthcare Resources) based exchange is a big focus of recent federal regulations. Carequality’s FHIR Implementation Guide is published and ready for Implementers to quickly start rolling that out, in addition to query-based document exchange, enabling simple and nationwide scalable FHIR exchange. Additionally, other forms of exchange, such as subscription-based notifications, electronic case reporting, and more are available or soon to be available through the Carequality Framework.

If you are a provider whose EHR does not currently support all of those forms of exchange, or if you are a health IT developer who does not support those for your customers, I highly recommend selecting a technology partner like Kno2 who is committed to supporting new and emerging standards, and can offer connectivity to all of those forms of exchange (and more) through a single connection.

More than ten years ago the move to EHRs sparked the transition to electronic patient data exchange, but while they may have laid a foundation, disparate systems, workflows, and content requirements have created barriers to exchange. With information blocking enforcement in effective April 5, 2021, I predict the market will respond with a demand for easy connectivity to the entire healthcare ecosystem regardless of the communication preferences of the receiving provider.

If you are looking for a technology partner who can support all of your connectivity needs, contact us at www.kno2.com/contact.

Read More: The Carrots and the Sticks to Achieving Interoperability – Kno2

Disclaimer: Please note that this article provides general information and is merely intended for educational purposes and does NOT override your need to exercise sound professional judgement in specific circumstances.

Additional Resources: ONC has created a number of good resources around these requirements, and others have published guidance as well. In fact, the Sequoia Project—which was previously selected as ONC’s Recognized Coordinating Entity (RCE) for the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA)—is now in their second run of a 14-week Information Blocking Compliance Boot Camp, in addition to ongoing Subgroups working to better understand information blocking requirements for each of the “actor” categories.